In late 2009, Bailey’s latest tourer construction method, Alu-Tech, was born and the company’s marketing team was soon telling us how one day all vans would be made this way. But that wasn’t quite the case. Within a year or so, other production techniques appeared from Swift and Elddis.

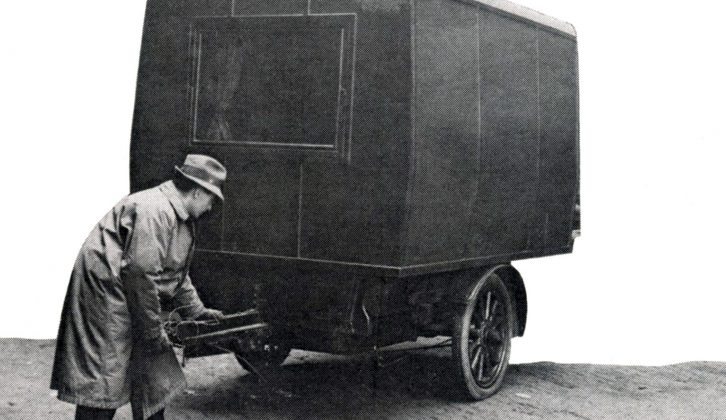

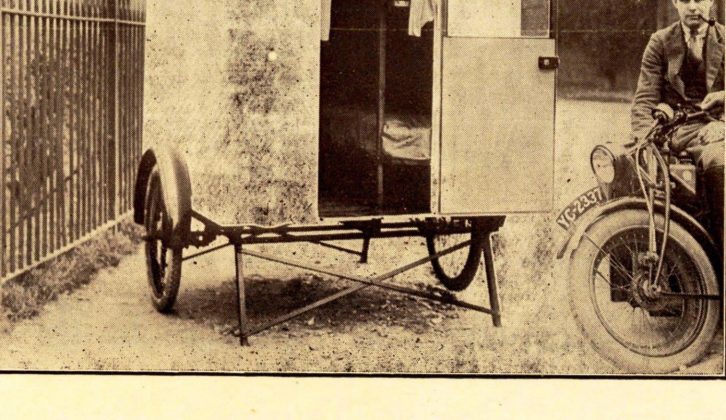

So is it true to say that caravan construction hasn’t really progressed? Not at all: in the beginning, ‘primitive, heavy and not very durable’ was the best description of many early vans.

Starting from scratch

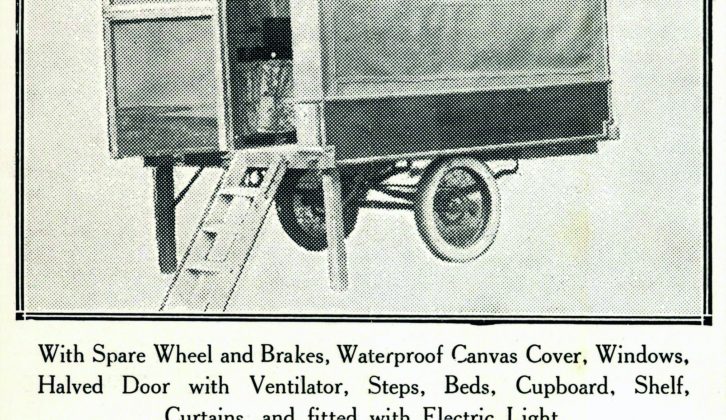

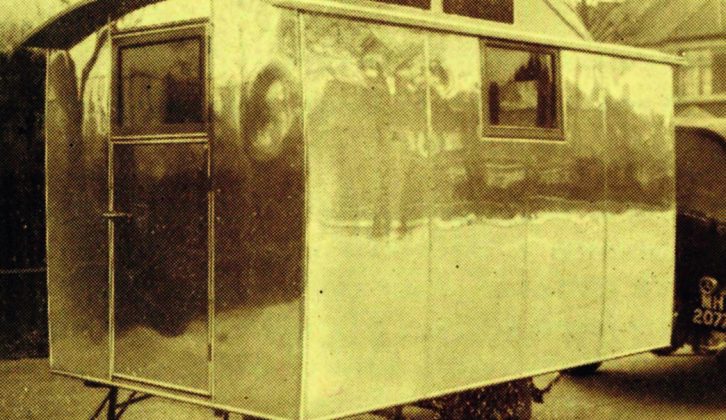

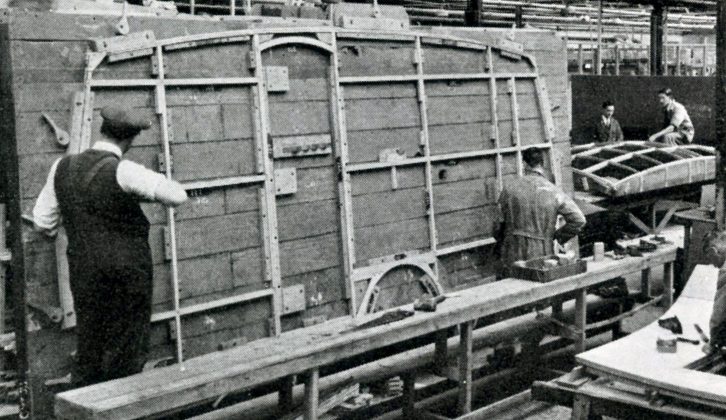

The reason? Materials, mainly. By the early 1920s, caravan construction consisted of a mixture of panelled sides and canvas. But methods progressed to a framework that was then panelled in plywood – usually marine ply. Lightweight, cheap caravans had spruce framework held together at the joints by panel pins, but put any stress on the framework and those joints came apart. On quality tourers, ash or other hardwood was used for the frame, with half-lapped joints held together with metal braces. These vans also used plywood, but it was panelled with aluminium sheets.

Soon hardboard was being used in cheaper single-panel caravans, but in cold weather these tourers were far too chilly to be comfortable, so manufacturers switched to double panels, many with an air space between them for insulation. Cork and other materials were often used to fill this gap. Roofs were usually plywood covered with stretched canvas, which was then given several coats of lead paint. By this time, the chassis had also changed to steel. The framework was built off the chassis, then placed onto it after completion.

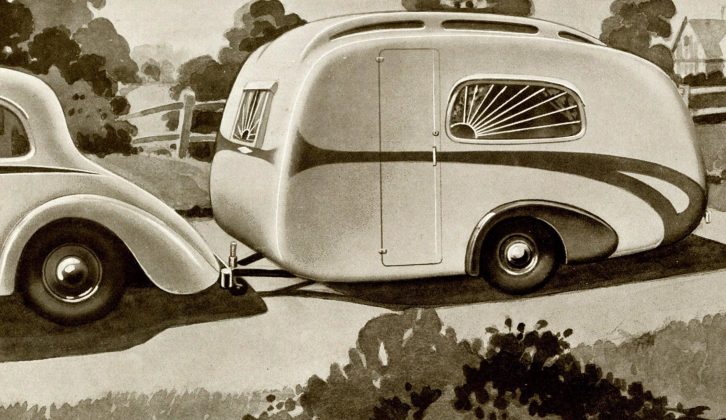

During the 1930s, framework was covered with hardboard or aluminium, but tourers needed repainting on a regular basis. With more aerodynamic profiles, however, and the advent of Art Deco, caravan construction was about to step into the future.

Airlite Caravans was formed by Clifford Dawtrey in 1935; by 1937 it was using Bakelite plastics in its tourers. The process was labour-intensive and involved hours to ‘iron’ the plastic on over all edges of the van. If the Bakelite wasn’t applied correctly, though, it cracked, exposing the corners to water and damaging the panels.

From ply to steel

Airlite was short-lived, but Clifford Dawtrey created Coventry Steel Caravans and revisited its construction methods. An all-steel model emerged, complete with a sliding sunroof. An ash frame and steel panels were added to the framework. This again was a labour-intensive process, as well as an expensive one, but the results were superb. Named the Phantom Knight, this steel van was strong, aerodynamic and had advanced features, yet it was costly and heavy. Dawtrey built another variant using leathercloth as an external finish, but the company folded in late 1939.

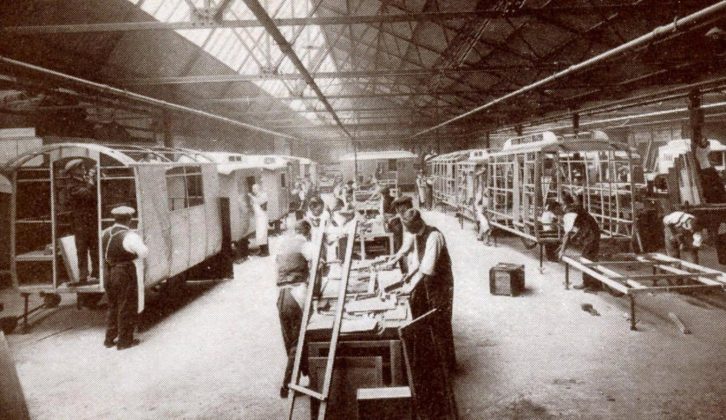

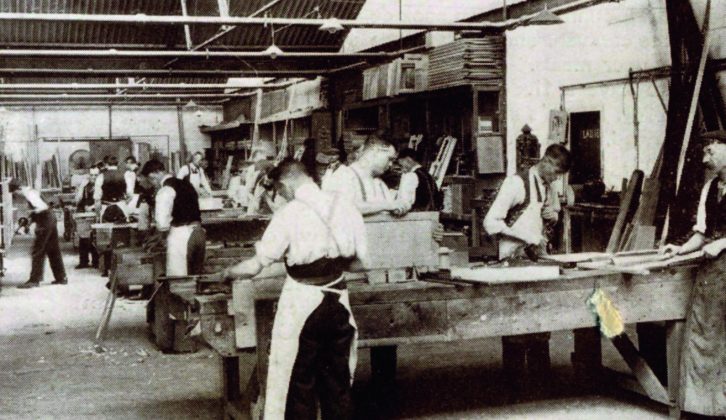

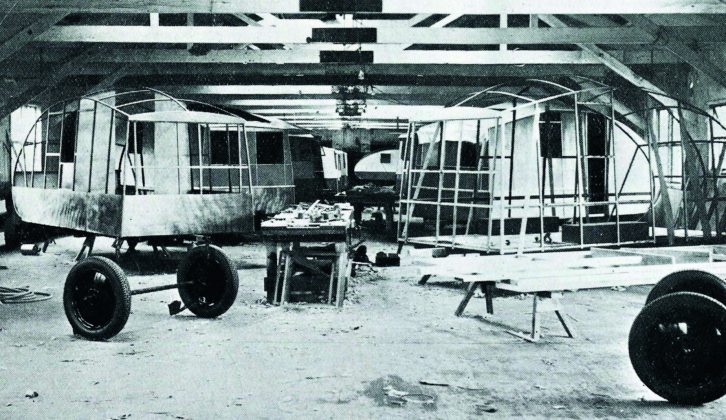

The Second World War disrupted caravan manufacture but it also pushed van makers to look at new building techniques. Some companies borrowed ideas from aircraft manufacture. Eccles developed jigs that built the framework; then the tourer was assembled on a production line. Hardboard was still used, but some manufacturers tried aluminium, which was also tested for roofs, replacing doped canvas.

Other companies developed new ideas. In 1948, Paladin used sections of wall that slotted into place on the chassis. The revived Coventry Steel employed a similar method, but Dawtrey’s ideas of plastics in van construction were being employed in Coventry Knight Caravans from 1947. Moulded Perspex sections in the roof and Perspex windows were used. Some makers tried aluminium frameworks, but this was expensive and added weight. Chalfont Caravans used metal sections based on aircraft manufacture techniques.

During the 1950s, caravans were still being built as they had been in the 1920s and 1930s, with timber frames, double-panel ply sidewalls and a single-panel roof. Early Streamlite Rovers (Sprite) first used Holoplast, a heavy material that proved expensive – and buyers didn’t pay for costly new construction.

Insulation was added to timber frames, plus aluminium was becoming cheaper so hardboard was gradually phased out. However, forward-thinking caravan manufacturers began looking into a promising new material called glass-reinforced plastic (GRP), aka fibreglass.

Not only was GRP more durable, but designers could finally come up with some aerodynamic designs. Willerby Caravans near Hull designed a large van named the Vista. Its fibreglass was seamless and the company boasted that it was ‘leak free’, claiming that GRP was the future of caravan construction. Willerby branded its construction ‘Armour-Plas’ and by 1956 it had spawned the more popular Vogue model.

The Vogue went further, adding a floor moulded from GRP. The chassis was almost dispensed with by using a design that is virtually the same as that found in modern tourers today.

Other makes joined this caravan design revolution. Berkeley Caravans used GRP in a new model named the Delight. Made of two joined halves, the Delight used GRP to its best capabilities. Berkeley named its GRP process ‘Fibreform’, but it proved more successful for its Berkeley Sports car bodies than its vans. Paladin used a GRP mould for the top half of its tourers, leaving the lower panelling in aluminium.

Luxury methods

Top-end maker Freeman Caravans moved to all-GRP constructed caravans in the mid-1950s. However, at this point, GRP was still expensive and heavy. Willerby dropped the GRP method altogether, as did Berkeley which went into liquidation. (It started up again briefly with the GRP Encore, but was short-lived.) Luxury brands Siddall and Cheltenham both opted for GRP but only for the front and rear panels and the roof of their vans.

In the 1950s, Berkeley introduced the Europa, an all-steel model that the company hailed as a caravan of the future. Testing was extensive, but the public didn’t like the profile, price or weight, and many rusted away.

By the 1960s, Carlight had tried out sandwich sidewalls using a GRP exterior with no seams in the sides. This was years ahead of its time, but Carlight customers still preferred the old coachbuilt style, although front and rear panels were now GRP.

In 1964, Regency, a northern company, used GRP again for all panels that were then screwed together in sections. Three years later, the company developed a sandwich construction for floors – at a time when most other manufacturers were still using hardboard or even tongue-and-groove flooring.

The problem with GRP

GRP had been mastered in terms of caravan construction, but the moulds needed for it weren’t cheap. It wasn’t until late 1968 that Hull-based Ace Caravans invested heavily into GRP for its 1969 tourer range. Using full-height front and rear panels, this GRP method was designed to give the mid-priced buyer a more reliable van. Ace claimed that leaks would be a thing of the past, while at the same time giving its caravans a modern appearance that competitors couldn’t match. However, GRP panel joints in the aluminium roof proved weak, and within 12 months Ace dropped the idea.

During the 1970s, sandwich-constructed floors were introduced, but in general, construction stayed the same. Silverline Caravans tried using the sandwich method, an idea it had seen in the US, but again, manufacturing problems and expense killed the idea.

Then Eccles, with help from Ogle Design, came up with a new concept that also incorporated extensive plastic construction. Van framework was still made of timber, but the sides were aluminium, and both front and rear panels were made using plastic moulds. The chassis ended at the axle, the floor was supported by wood, and the roof was also made using plastic side moulds. Innovative, for sure – but not a big success.

In 1974 the Ci Group, of which Eccles was part, developed the idea of injecting foam into the sidewalls and ends of caravans. Strong as well as lightweight, it also retained heat – but it cost over a million pounds to put in production, so only the Europa and Eccles models benefitted from the process.

A pricey process

Construction was taken to the next level by Monolite Caravans. It built a special bonding press, using it to construct the side and end panels but also using one-piece aluminium sides. Monolites were mid-priced tourers, but manufacturing them proved expensive and, although sandwich construction proved durable, the caravan buyer of the time was not convinced.

Motorhome-maker Dormobile, which had dabbled in the tourer market in the early 1970s, re-entered it by introducing a range of newly constructed models. Sandwich construction was used for sides and ends, but the company went further still. First a steel frame was built around the chassis, then the van sides were glued to the chassis. The range was a success for several years, as was the construction method.

Swedish manufacturer Cabby used sandwich sidewalls filled with polyurethane, then bonded using 70 tons of pressure. The roof was one piece and included the top, front and rear panel. The Cabby’s roof proved so strong it could support a car and several workers.

By the end of the 1970s, the Fisher Caravan company produced the angular little 3m-long Petite. Its sides were laminated, bonded one-piece units; aluminium edging allowed these to slide into place, where they were then screwed together. The roof was a one-piece unit that screwed onto the sides. By the early 1980s, bonded sandwich sides were employed by most manufacturers as costs came down. The process was strong, light and seemingly reliable, and it looked set to stay.

In mid-July 2009, however, Bailey developed a new non-wood framework technique, which involved a one-piece roof that clamped into position on the sides. Bailey was so confident in its Alu-Tech system that all of its tourers were made this way by 2011.

Following the leader

Elddis countered Bailey’s innovation with its SoLiD construction method, using strong bonding and a locking system that cut down on the amount of screws used, thereby reducing water ingress.

Swift also introduced the SMART method of production, which replaced a lot of timber in caravan bodies with a water-resistant polyurethane-based product. Swift then took things a step further with SMART HT, which incorporates a locking system and modern bonding glues, plus the timberless bodyshell with polyurethane blocks. The company also addressed the normal plywood sandwich floor system by eradicating wood from the process and using a ridged honeycomb matrix with a styrofoam core, making it lightweight and extremely strong and durable.

Since the creation of the touring caravan, construction has played a vital role in its development. In the last few years, it has probably played a greater part than at any other time in van history. Bailey began the construction revolution. The buying public took note. Now it is seen as an important factor in purchasing decisions. One thing is certain: the process of caravan construction will always move forward.

Lightweight, cheap caravans had spruce framework held together by panel pins