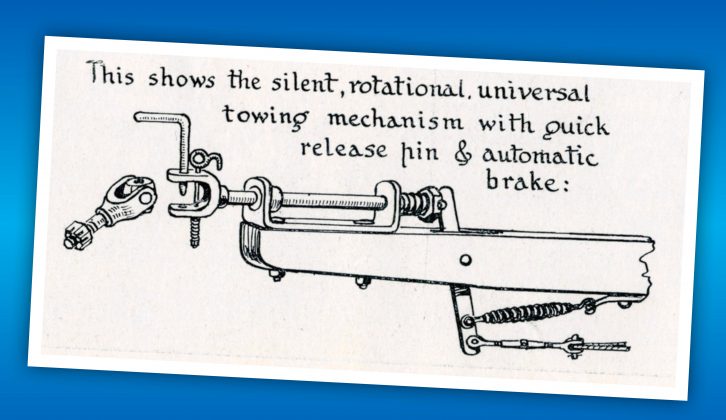

When the first car-pulled caravan emerged after World War 1, there was a seemingly simple solution to the problem of attaching the tourer to the tow vehicle: a leather loop on the caravan drawbar was just slipped over a hook at the back of the car. It soon became clear, though, that a more technical hitch solution was required to ensure the security of the connection and, of course, the safety of everyone else on the road. This developmental process would take a number of decades.

The next step forward took place in the 1920s, when pin couplings were introduced. Bespoke tow bars were constructed from angle iron before being bolted to car chassis. Caravanners usually asked a blacksmith to fashion this addition, but even if a mechanical engineer constructed a car’s tow bar, it invariably wasn’t tested! In either case, the job usually took several days and the customer was completely at the mercy of the artisan.

In fact, blacksmiths remained a link in the supply chain even as the 1930s came along. Despite the Depression, the middle classes enjoyed new affluence and aspired to caravan ownership, which until then had been the exclusive domain of the rich. This growth in demand not only kept the blacksmiths busy, but also led to a glut of cowboy garages rushing to offer a similar service.

Unfortunately they didn’t always fit their tow bars to the strongest part of the car, and the workmanship was often poor; it wasn’t unheard of for a caravan to become detached from the tow car en route! One other alternative was for the competent caravanner to fit their own.

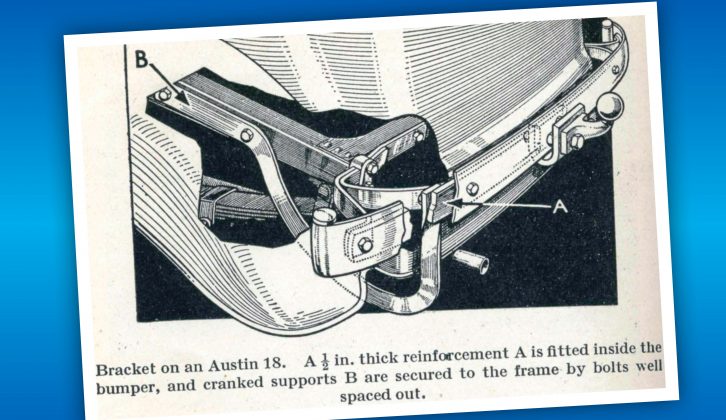

As the design of cars progressed, so did that of towing brackets. By the 1930s these were usually fixed to part of a steel-reinforced bumper; some dealers even had workshops that fitted towing brackets to customers’ cars.

When there were any fitted, the towing electrics were simple. Most tourers had no rear lights at all; those that did often possessed just one, coloured red and on the offside. However, one major innovation that took place during this decade promised to change towing in a big way: the introduction of the 60mm ball coupling. It took a while to take hold, though, and breakaway vans and bodged tow bars remained a feature of the touring landscape right into the 1940s.

It was in the 1950s that the groundwork was laid for the true steps forward in tow bar development. At that time, many cars were moving over to monocoque bodies; in other words, unitary construction with an integrated chassis and body. This forced designers to rethink tow bar fixing points. One was Chester engineering firm Dixon-Bate, which had produced trailers and caravan chassis since the 1930s and was now considering developing tow bars as off-the-peg products for popular car models.

One of its employees was Colin Witter, who had extensive knowledge of the field. He wanted tow bars to be safer, and to fit securely to the strongest points on the car. In 1950, Colin set up his own business in Chester, Witter Engineering, to design tow bars. The original plan was to outsource their production, but he soon brought together a small team of engineers and expanded into manufacturing. As such, the company was ready when the popularity of caravanning took off in the 1950s; although small engineering firms tried to cash in on the demand for tow bars, Witter was already way ahead.

In the years that followed, Colin worked hard on testing his tow bars and persuading car makers to send new models to his headquarters, where brackets could be designed especially for them. In addition, he introduced another popular innovation: tow bars that didn’t spoil a car’s looks.

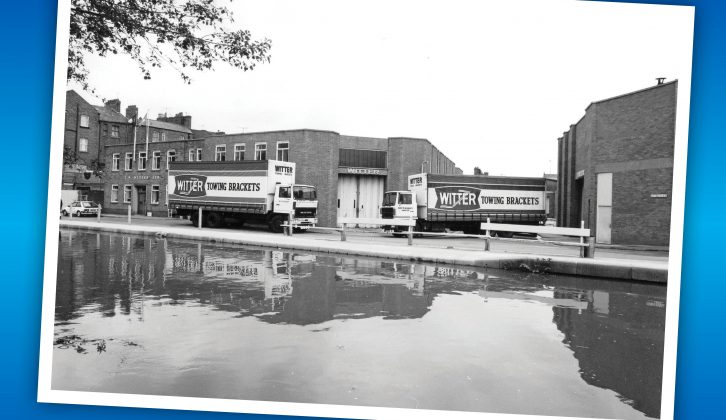

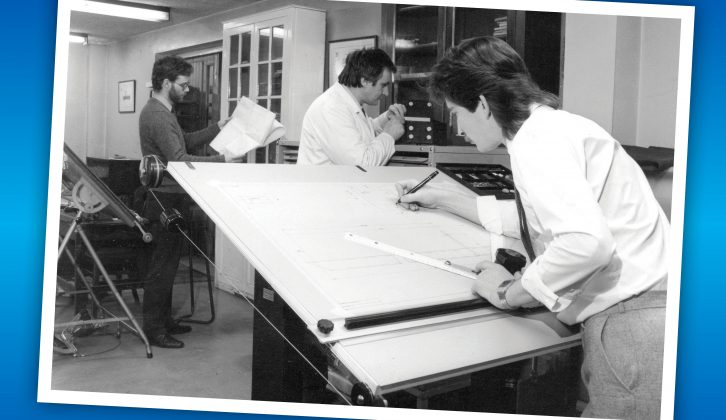

Development continued into the 1960s; products included Witter’s Mongoose stabiliser and a 50mm towball on a rubber mount that was designed to absorb surface shocks. This was also the decade when Witter moved to larger premises and Colin’s son, Brendan, joined after a spell with Austin Motor Company. His younger son, Rodney, followed in the early 1970s and took on the responsibility for design.

Witter became involved with the annual British Caravan Road Rally around this time; it was a crucial testing ground for tourer manufacturers and suppliers. Witter even won events, which proved its products’ durability and reliability under difficult conditions, and thrust the brand into the limelight.

Meanwhile, the company was working on ways to make its products easier to fit. By this time, rival brands were also entering the market, although they had a lot of catching up to do. In the end, several of these newcomers fell away because of stringent new regulations governing design standards. Witter’s experience, however, meant that it survived.

Colin Witter would keep on devising tests for his tow bars to ensure they met his own exacting demands. In the 1980s, he also came up with a gruelling PR stunt: son Brendan was sent off in an Austin Metro 1300 towing a Sprite Alpine hitched to a newly designed Witter bracket. He drove the 878 miles from Land’s End to John O’Groats in 18 hours, successfully promoting the UK’s top tow bar brand.

Mid-decade, Witter invested £150,000 in robotic welding, which ensured greater precision. Four machines were installed to boost production and help meet growing demand from abroad.

When Colin passed away in 1986, his legacy was a company that had grown from producing a few thousand tow bars a year to one that was turning out more than four million. By the end of 2000, this figure had risen to over five million. More than 30,000 different jigs were stored and, though some are long gone, the company can still make one-off tow bars using original, carefully filed drawings.

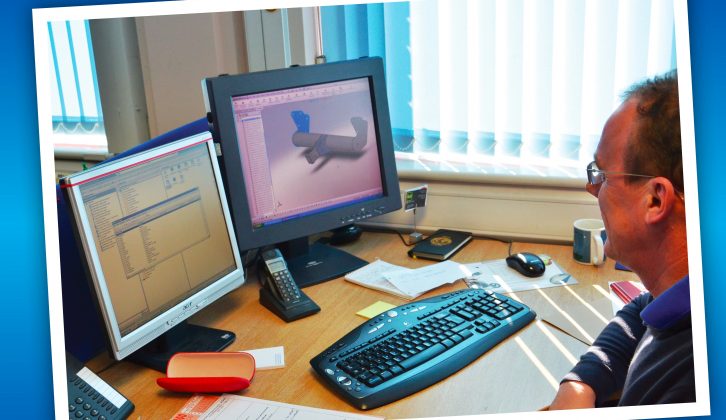

Witter’s continued growth necessitated even larger premises than those it had occupied since the 1960s, so the operation was moved to its current Deeside plant. More new technology was added and, by 2010, more than £3 million had been invested.

Today’s safe, carefully designed tow bars are light-years away from the crude hitches that emerged from the blacksmith’s forge, or the DIY efforts of early enthusiasts. Those days are long gone now, and Colin Witter’s foresight certainly played a huge role in that development.

Colin Witter would keep on devising tests for his tow bars to ensure they met his own exacting demands